TL;DR: This post covers creating and coordinating a feedback process. It includes takeaways from what I did right (and wrong) on Encounter in the Radiant Citadel.

This is part of a series on Project Management for TTRPGs. Stay up to date on this series by subscribing:

The Feedback Process

Feedback processes can vary wildly and have a lot to do with shared expectations and trust. If you tell someone to "edit your adventure," this could mean that they read your adventure and provide comments. Alternatively, this could mean that the author turns in their adventure, and then the editor takes over the draft, rewriting whole paragraphs.

Regardless of what process you use, feedback is one place where you need expectations to be crystal clear:

What type of feedback is needed

Who gives feedback and when

Your feedback process

What to do with conflicting feedback

Points 1 and 2 were covered last post. This post will cover point 3, feedback processes!

Ways to Give Feedback

Make sure both the editor and the author have the same understanding of how feedback will be given. Editors can give feedback as:

A separate document with thoughts on the writing

Comment on the document

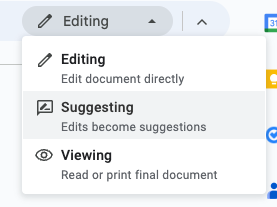

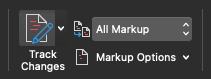

Make changes but keep a history of what changed (In Google Docs turning on Suggestion mode and in Microsoft Word turning on Track Changes)

OR you can skip feedback, handing the writing straight to an editor or project lead (which I'll describe in my next post)

Tagging Feedback: Red/Yellow/Green

If you have editors giving feedback, make sure that the feedback is crystal clear as to what the author is supposed to do. One aspect of this is to denote the importance of the feedback and how the author should handle it—is this required feedback or more of a personal opinion?

An easy way to handle this is by tagging your feedback. There are a few different approaches to tagging comments. One approach I recently learned from Lydia Suen, lead writer on The Stormlight Archive TTRPG. For every suggestion you make, you tag it as red, yellow, or green, which mean the following:

🔴 Red: Absolutely required feedback; this will not be published unless it's fixed.

🟡 Yellow: This feedback should be addressed. If the author can't easily address it, they should discuss it with you.

🟢 Green: Suggestions, nice to haves, optional feedback.

The Red/Yellow/Green tagging approach has been working well for the Stormlight team, and I recently used it during feedback for Jukebox.

Incorporating Feedback: Questions to Ask

Make it clear how feedback should be addressed. Here are the questions your process should answer:

If you're using document comments, how should those comments be handled? Who closes the comments?

Who's responsible for incorporating feedback, the author, the feedback giver, or someone else?

If the author makes a change, will the editor need to review to certify that the issue was resolved?

Who determines whether the feedback has been dealt with?

Tracking Feedback: Sign-Off Tables

Feedback loops should be part of your project schedule, with time allotted for the back and forth. If you're using a tool like Google Sheets or Notion to track work, editing and playtesting should be tracked there. In addition, I also use sign-off tables.

Back at Google I used sign-off tables; this is an administrative section at the top of the document where stakeholders can sign-off on things like blogposts, marketing announcements, or video scripts. That's a lot of business-speak:

Signing-off is saying that you're good with the content being published

A stakeholder is someone that needs to be consulted and happy with whatever you're publishing

A sign-off table clarifies who must be happy with the document and tracks whether they are or aren't happy. As a project lead, you can look at the table and know at a glance whether a project is ready to move to the next step, and if it's not ready, who you need to check-in with.

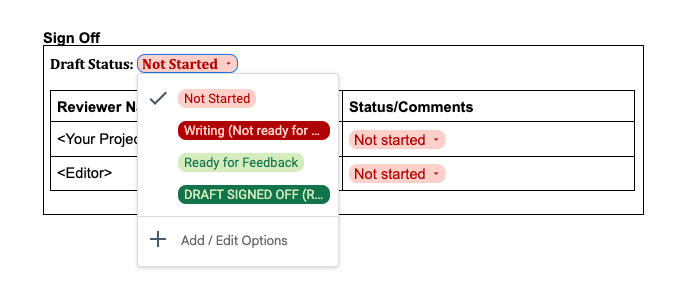

In TTRPG work, your stakeholders are likely the project lead(s) and the editor. Sign-off can be a way of saying, "I'm happy with this moving to the next step of the creation process," whether that's another draft or layout. Here is an extremely simple sign-off table that you can add to writing templates in Google Docs:

To use the example sign-off table, add this table to the top of the template you give authors. It tracks the draft's status, both whether it is ready for feedback and whether the various stakeholders are done and happy with it moving on to the next stage.

The draft statuses are:

Not Started

Writing (and not ready for feedback)

Ready for feedback

Signed off

Each stakeholder can then mark whether they've:

Not started review

The review is in progress

The review is finished, but the draft needs changes

The draft is signed off

You can also include instructions in this table, such as directions for where to submit the draft, a link to an editing checklist, an example, a template, and so on.

Encourage Positive Feedback

This is a less technical point than everything above, but equally important: Make a point of providing specific positive feedback (and encourage your editors and collaborators to do the same). Sometimes we assume feedback is always about pointing out where to make improvements, but telling someone where they succeeded is just as important. Your collaborators should know when they're doing the right thing, so that they keep doing the right thing. So be specific about what they're doing well – you can say generally "great job", but a bit of specificity shows you were paying attention and makes it more clear to them what you liked.

Second, positive feedback is an easy way to boost morale and show appreciation for someone's work. It recognizes that we are not purely capitalist robots, grinding out content sprockets for money. We want to be good at what we do, we want to produce meaningful art - so celebrate it when you see it!

A Case Study: Encounters

Alright, let's talk about the feedback process for Encounters in the Radiant Citadel. This was one of the areas where I learned a lot and that I'd focus most on improving for future projects.

The Process

Who did the editing: Encounters had 9 collaborators who were all responsible for writing an encounter and also editing two encounters. I also planned to review all of the encounters myself.

How many rounds of editing: We had two formal rounds of feedback before layout. In the first round of feedback, the writers were responsible for submitting an outline, and the editors focused on developmental editing. The second round of feedback was for copy-editing to match the D&D 5e style guide and project template. Each of these rounds of feedback involved two collaborators giving feedback. After layout, there was also a final round of proofreading which I'll speak about in a later post. I decided to have different collaborators for the developmental editing phase and the copy-editing phase, so each encounter got feedback from four different collaborators.

The process: For each round of editing, I made a spreadsheet with editing assignments. Collaborators marked when they were finished editing.

All of the contributors had access to a bunch of resources about editing, most notably an editing checklist.

What Worked

Taylor is amazing: So that was the plan, and we followed it, with a notable addition: in the middle of the process, Taylor, who was by far the most seasoned D&D 5e writer on the team, essentially volunteered to edit the entire collection in addition to her assigned encounters.

While it was not planned from the start, having a single skilled editor had advantages. It just is more effective to have a single knowledgeable person reviewing all content than a group of newbie editors. When collaborators edited, they needed to learn the D&D 5e style guide on top of doing the actual job of editing. As mentioned in the Guidance post, the editing checklist was an invaluable resource—still, it's impossible to make any checklist that fully replicates editing expertise.

We learned a lot: One of the advantages of having a skilled editor and collaborators both giving feedback is that we all learned a lot "on the job". We could see what we caught and what others caught. I left the project having a far better understanding of how much skill it takes to edit to the 5e style guide and was a more competent D&D 5e editor.

Our two phases of editing worked: Splitting editing into developmental editing and copy-editing worked well. I'd recommend having at least two phases of editing, so you can spend the first phase focusing on bird-eye issues and leave the second phase for copy-editing.

Peer feedback: Including peer feedback, whether it is a requirement or optional, has many benefits. Authors appreciated that their work was read by 4+ team members and we learned a lot more from each other. We also became more invested in each other's work. I'm not sure I would run a project where this is the only form of feedback (or that I'd run it in the same way), but I will always include the opportunity for peer feedback.

What I'd do differently

Establish what edits are required and who gets final say: Here's the big mistake I made – I started this project without making it clear who would get the final say about edits. Was an author allowed to go over word count or not match the D&D 5e style guide? Technically no, we'd all agreed to a word count and matching the style guide. But it was unclear what to do if there was a problem. All that editors were required to do was to point out if they thought there was an issue. Were the editors required to follow-up that the issue has been fixed? What if the author got confused and did the wrong thing? Was it OK for peer editors, myself, or (later) our newly minted senior editor to just go in and cut words or make edits to match the style guide? Two problems arose from this:

Style guide errors and word count errors were still present late in the process

There was a lot of negotiating, confusion, and back and forth during editing, which slowed the process down

If I do peer editing in the future (as opposed to having a sole editor), I'd make the following changes:

Add an explicit "sign-off" step, where each editor would sign-off that the writing matched the style guide and then the project lead would sign off. Do not have the authors be the ones who "check themselves" off as ready to move to the next step. I did have a rudimentary form of sign-off, but it was unclear who needed to sign-off and when they should sign-off (should they sign off after giving comments? What would happen if there was a disagreement?)

Editors would be instructed to tag their feedback as "Optional" or "Required." All style guide edits would be "required," with other required feedback at the editor's discretion.

Everyone would know that if there was disagreement over a required edit, I, as the project lead, would get the final say. Depending on the project, I'd consider adding a "work for hire" term to the contract and explaining that to authors when they onboard. I’ll speak more to this in my next post.

Strict word counts for your first editing pass: I talked about word counts previously, but just to drive things home, set word count expectations on your first pass. To quote a collaborator "Feedback I received [on my first draft] ended up being null because I had to cut so many things from my encounter." Authors sometimes wrote two times over word count and then got editing feedback on an encounter that was nothing like what they would eventually submit after cutting out half of the text.

Consider hiring an editor: See more about this in the last post.

Conclusion

Feedback is the bread and butter of collaboration; it's one large benefit you get from working with others. It can be one of the most rewarding parts of collaboration if managed well (and one of the most frustrating if managed poorly). So plan your feedback process!

Big Bad Con Online: 24 Hours of Industry Talks

If you're reading this far it's probably because you're involved in TTRPGs. This past weekend was Big Bad Con Online, which had 24 hours of talks about the art of making games, all of which have been uploaded to YouTube:

I was on the Stronger Together: Peer Collaboration in TTRPGs panel, moderated by the talented Nala J. Wu (Art Director and Award Winning Illustrator). The panel included Dominique Dickey (Creative Director of Sly Robot Games), Taylor Navarro (Producer of Tales from Sina Una), and Superdillin (Host of the One Shot podcast):

The other panelists brought a wealth of knowledge and different perspectives to the advice I give here—give it a watch!

Over and out,

- 🫙 👁️ 👁️